Essay to accompany the group exhibition

Shoot the Works: unwelcome participation in non-participatory art

at Blip Blip Blip, Leeds, March 2013

FESSING UP

LIBERAL democracy functions on a balance of assumptions and assurances. Out on the street, it is assumed that we, the public, will behave decently to one-another and within the rule of law. In return, we are assured that certain measures are in place so as to safeguard us from the wayward actions of others, and punish the perpetrators of such actions should these safeguards fail. Transparency and accountability are central to this operation, the former being a prerequisite for the successful enacting of the latter. Democratic life is public life, and vice versa. If too many things go unsaid, and if people are not held accountable for their actions, then we have bad democracy. Putting on an exhibition is no different.

SHOOT THE WORKS is not an exhaustive or comprehensive study of its subject: the vandalism and intentional damage of works of art by independent citizens, be they artists or civilians. It does not include actions by governments or mainstream political and religious bodies, such as the Protestant iconoclasts of the mid-16th century, or the destruction of public monuments in the former Soviet Union (a subject interestingly explored by Laura Mulvey and Mark Lewis in the film Disgraced Monuments, 1993); to cover these events would take a much larger exhibition. It also does not include damage to artworks that seem calculatedly provocative and, therefore, engender outrage and the possibility of violent reaction almost as part of their design (Marcus Harvey’s Myra, 1995, for example). I chose instead to include damage done to works that the majority of people seem to have little or no issue with, where the motive for the attack feels less a reflection of public consensus or a flexing of ideological power, and more the expression of an acute, intimate compulsion. The artists were chosen because I feel their works reflect the different aspects of this issue, each work offering a distinct and important take. The historical examples were chosen for the same reason, and because they looked right. That is to say: one, an image relating to the incident was available; and two, the available image works – that, in lieu of the original object, it successfully documents the result of the action, and conveys the visceral and physical reality of the act. These images, I think, still carry some of the power, potency, and vigour of the deed; stabbing a knife through a painting is not like stabbing a person, but it’s not like spreading butter either.

FOR the sake of ease, I will cover the unaffiliated actions of this motley gang of strays under the umbrella term participation – a word both consistent with art-speak parlance and imbued with suitable euphemistic blur; it allows us to talk about multiple things at once. SHOOT THE WORKS is a record of personal responses to art works, responses deemed improper and, on occasion, immoral by the institutional powers-that-be. SHOOT THE WORKS is not an attempt to somehow legitimize or validate the actions and events that it records – they don’t need validation, they need airtime. All these events occurred in the public realm, so there is a democratic responsibility to open them to public scrutiny or, at least, scrutinize them in public. Exposure is not absolution, and a little creeping daylight does not promise the perpetual glare of publicity and promotion. With evidence comes examination and critical evaluation, private readings and public hearings, disagreement or accord. We shouldn’t talk about things we know nothing about – that’s bad democracy.

CASE NOTES

ABOUT violence against artworks I have three questions. First, what actions constitute as violence, as in: how far does physical participation need to go for it to be deemed violent? Second, in what ways can we think about the perpetrators of such participation, given that we’re talking about violence against objects and materials, not people, but things? And third, is there a pre-existing lexicon that can be appropriated in order to discus these matters, without resorting to moral judgements and while avoiding the calculatedly amoral language of aesthetics, or can a new specialised vocabulary be fashioned so as to operate ethically between the consensus of the masses and the impulsive needs of the individual? In short: what’s happening, who’s doing it, and how can we talk about it? Like any good crime story, it’s the what, the who, and the how.

THERE is a great book out there called ‘The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution.’ Its author, Dario Gamboni, attempts to answer these questions and more, examining with what he calls the “heuristic value” of “aggression directed against art”: “If one considers the autonomy of art not as an atemporal essence but as a historical and historiographical construct . . . Then it follows that attacks represent a break in the intended communication or a departure from the ‘normal’ attitude shown towards them.” It almost goes without saying that I am with Gamboni on this. ‘Almost’ because what he’s suggesting isn’t easy to acknowledge, and to agree means to denounce completely the idea of the innate sanctity of art, that its (non-monetary) value is intrinsic, and its contribution to culture and society irrefutable. Even in a time when the public seem quick to accuse the artworld of shysterism, seeing it as the refuge of greedy, elitist, self-involved frauds, even then the animosity is seldom aimed at a universal target. If one person hates contemporary art, they may find value in Renaissance art. If Johnny hates ‘fine’ art, he may find value in fashion or design. If Susanne hates painting, she might like the movies. And so on and so on. Rarely is it a blanket condemnation of all visual practises, there is perceived to be some value, somewhere, always. This is one reason – an important one – why you hear people say they don’t ‘get’ art. Because regardless of the quality of the art work in front of them, and regardless of whether they actually like it or not, the perceived value is such that it can only be their fault as ‘uneducated’ or ‘ignorant’ viewers. Art’s value is fact; an audience’s intelligence is not. (Some people just don’t give a shit, and, well, that’s just cool.) So if Susanne or Johnny want to express their frustrations, of course they’re going to do it in an ignorant, uneducated manner. And if they’re extraordinarily troglodyte, this might mean walking into a museum and literally attacking the art, their insufficient intellect causing them to resort to blunt brute force. Shocking and ultimately meaningless, such things are the actions of criminals and madmen. Well, that’s how the theory goes.

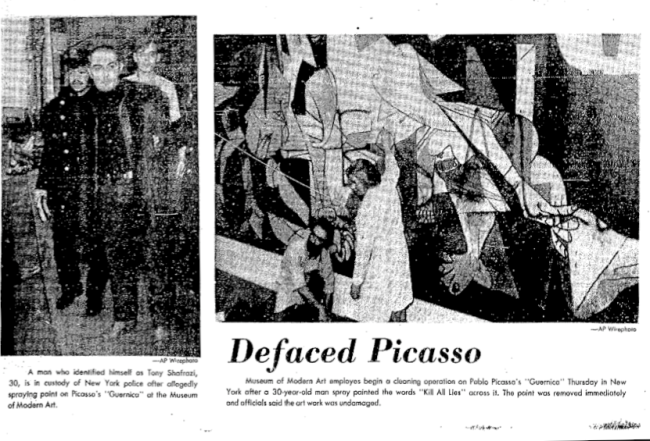

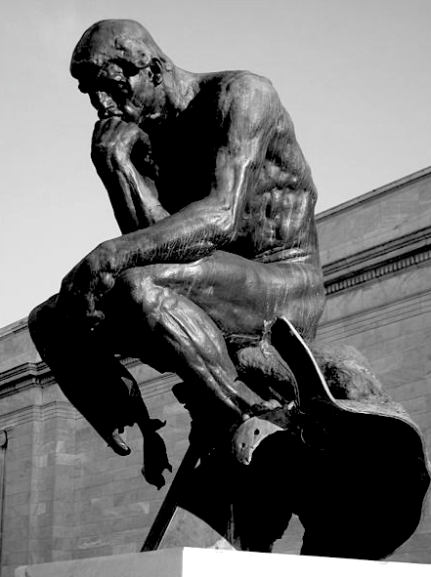

MOSCOW, 1913: Abram Balashov enters the Tretyakov Gallery and uses a knife to attack Ilya Repin’s painting Ivan the Terrible and his Son Ivan, cutting three deep scars down the face of the elder Tsar. Balashov is immediately declared insane and so does not stand trial. A year later, Mary Richardson attacks Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus in the National Gallery in London, again with a knife. The Times prints the headline, ‘Deranged Suffragette Attacks the Rokeby Venus’; the story runs across two whole pages. Richardson gets six months jail time, the maximum sentence for an offence of its kind. Beyond the portico outside the Cleveland Museum of Art, stands the last Thinker statue cast by Rodin himself. In 1970, it’s bombed with dynamite by the left-wing militant group The Weathermen. Due to Rodin’s involvement in the making, the work is not fully restored and still bears the damage from the attack to this day. No-one is arrested or questioned about the bombing. New York, 1974: a young Iranian artist called Tony Shafrazi spray paints the phrase ‘KILL LIES ALL’ directly onto Pablo Picasso’s painting Geurnica, then on show at the Museum of Modern Art. The painting is heavily varnished and thus easily resorted. Shafrazi is arrested and charged with criminal mischief. Despite witness reports to the contrary, the New York Times describes him as “enraged.” This whistle-stop historical tour visits some of the main cultural centres of the 20th century, and maps, albeit very loosely, an interesting route through the complex convergence of private intention, public action, legal consequence, and social reaction. Although the actions were varied in design and approach, a cursory look at the targeted art works reveals some interesting commonalities: all were well known and more-or-less popular; all depict human figures; and all were on display at state-funded institutions when the attacks took place. These three details are important.

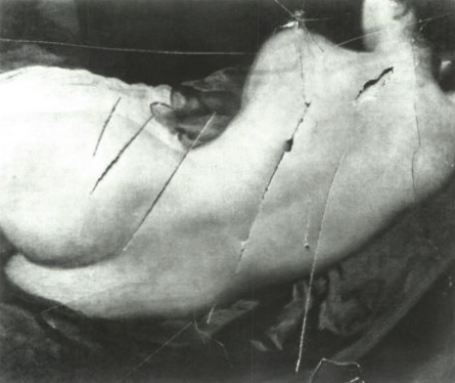

BALASHOV was an icon painter and an Old Believer, a Christian denomination founded after the Russian Orthodox Church made several major reforms between 1652-66. Ivan the Terrible, Balashov’s pictorial victim, had died in 1584, and there is no connection between the infamous Tsar and the church reforms that so angered the Old Believers. Religious fervour seems an unlikely motive. Repin’s painting depicts a distraught Ivan having just brutally, but accidentally, beaten his eldest son to death. He cradles the young man’s body and stares hauntingly out of frame, his eyes as blank as they are mad, his son’s blood pouring over his hands. The palette is rich and heavy, using mostly varying shades of red. Witnesses to Balashov’s crime say he screamed, “Too much blood!” as he began to slash the painting. (Was this a clear sign of insanity? Or was the whole thing one painter’s scathing critique of another?) As Balashov never saw a courtroom, there is little written about him or the events surrounding his participatory action. A black and white photograph is all that survives, showing the three cut marks in severe close-up. The ripped canvas gapes like deeply torn skin, powerfully foregrounding the surface of the painting. The original narrative of the work is irrevocably disrupted; the characters remain, but the illusion is lost. The photograph recalls and pre-empts certain contemporary works: Miro’s burnt canvases from the 1970s; the cut and bunt photographs of celebrities in Douglas Gordon’s Self Portrait of You + Me series; and the punctured paintings of Lucio Fontana. The image of Balashov’s attack seems to somehow foretell these works and many others that followed.

RICHARDSON’S Rokeby… has a similar effect; the viewer jolted by the deep scars hacked into the back of this quintessential reclining nude. Unlike Balashov, her action was undoubtedly premeditated, fitting into a wider programme of suffragette civil disobedience. In advance of the attack, she drafted an explanatory statement outlining her intentions with great clarity and intelligence. “I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history,” she writes, “as a protest against the Government for destroying [Emmeline] Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history . . . If there is an outcry against my deed, let everyone remember that such an outcry is an hypocrisy so long as they allow the destruction of Mrs Pankhurst and other beautiful living women.” Pankhurst was the founder of the Suffrage movement and was on hunger and thirst strike in Holloway Prison at the time. As her imprisonment and maltreatment continued, so the suffragette campaign escalated, becoming wider in scope and more ferocious in method, but always avoiding what Pankhurst described as “men’s blood-shedding militancy.” Property became the main focus of attack, and the Rokeby Venus was an exceptional target. The National Gallery had acquired the painting in 1906, for forty-five thousand pounds, making headlines across the country. Newspapers ran several reports on the work and its perceived cultural, social, and, of course, monetary value. The coverage became a kind of hubristic clamour, entirely disproportionate to the artwork itself, and leaning uncomfortably toward pervy fascination. In this light, Richardson’s wrath seems warranted, and her choice of target inspired. The “outcry” she predicted did indeed follow and some of the more upset journalists christened her with nicknames like ‘the Ripper’ and ‘Slasher Mary,’ in crude, exaggerated reference to murderers and serial killers. Significantly, it proved the suffragettes right: in certain circumstances, against the right target, attacks on property can create the same reaction as attacks on people; violent protest needn’t cause blood-shed or cost lives; and a campaign of aggressive action can be conducted without giving up one’s morals. This was an important lesson, but perhaps not a new one – the Suffragette campaign forming a kind of sectarian iconoclasm.

ANOTHER great book out there is ‘Crowds and Power’ by Elias Canetti. This quote comes from it: “The destruction of representational images is the destruction of a hierarchy which is no longer recognized. It is the violation of generally established and universally visible and valid distances.” Canetti’s ‘distances’ are physical and metaphorical, and mutually contingent; action in one realm has consequences in the other. So when a physical boundary is crossed, a mental boundary is weakened; and repeated transgressions may wear down all resistance entirely. Museums cite this as the main reason so many acts of vandalism go unreported. They don’t want to encourage copycat attacks, so keep things in-house as often as possible. (This argument remains questionable, as museums are primarily trying to save face. As custodians of cultural property – owned by the public or on loan from wealthy donors – any attack on property under their care severely damages their all-important prestige.) But some participatory actions are too remarkable, and some targets too important, for the successful application of these strategies of containment.

AFTER Tony Shafrazi spray-painted Geurnica, MoMA had hoped to keep the event quiet, away from the press and out of the public eye. Shafrazi saw his action in political terms, turning to one of the greatest anti-war paintings in order to protest against the then-current war in Vietnam. As he said in 1980, “I wanted to bring the art absolutely up to date, to retrieve it from art history and give it life . . . encourage the individual viewer to challenge it, deal with it and thus see it in its dynamic raw state as it was being made, not as a piece of history.” (This probably isn’t what Picasso had in mind when he said, “an image is the sum of its destructions.”) Of course, this attempt to “retrieve” Picasso’s work “from art history” made the New York papers the next day. Conversation then shifted from the sheets to the studios, with various factions and figures chiming in. The Guerrilla Art Action Group commended Shafrazi for “freeing” the painting “from the chains of property,” and returning it to its “true revolutionary nature.” While an anonymous group of ‘art workers’ argued Shafrazi had “attempted to supress the artistic freedom of Picasso by infringing on the artist’s inviolate right to make a statement without censorship or parasitic ‘joining.’” MoMA kept its collective mouth shut and restored the painting – a simple job thanks to several layers of protective varnish. Shafrazi’s apparent naivety is disarming (and somewhat dubious), but he’s kept to the same story in all the years since, recently telling Interview Magazine, “The critical factor is to realize that [in 1974] the burning, the rage, the inhumanity, and the hatred that is rampant in American culture was really coming to the surface. In a climate like that, nobody pays attention to pretty paintings. The role of art was, I felt, very important and being neglected.” Shafrazi’s was a conscious attempt to contemporize a pre-existing work of art, which implies two things: one, that a work of art can lose its contemporary relevance, its ‘now-ness’; and two, that such ‘now-ness’ can be intentionally re-inscribed by contemporary figures. Both points are slippery and subjective (like all the best things are), as the first point neglects the fact that ‘contemporary relevance’ is, by definition, an ever-changing condition, and the latter point certainly sets a potentially dangerous precedent. But perhaps there is some validity to the idea of a contemporized artwork.

“BUT is it not even a more significant work, damaged as it is? No one can pass the shattered green man without asking himself what it tells us about the violent climate of the U.S.A. in the year 1970. It is more than just a work of art now.” These are the words of Sherman Lee, then-director of the Cleveland Museum of Art. He was talking about one of the museum’s sculptures, an original cast of Rodin’s Thinker, which had just been heavily damaged by a bomb attributed to the radical left-wing group The Weathermen. Immediately after the event, Lee and other senior museum staff had hoped to restore the stature to its former state, perhaps shipping it Paris so the Musée Rodin could attend to it, or producing an entirely new version from the original casts. The Thinker exists as a multiple; there are thought to be around twenty-eight original castings, with many more unofficial, posthumous, or physically-variant versions around. The one at Cleveland was the last casting overseen by the artist, and Rodin’s direct presence in the object’s history made Lee’s situation much more problematic – either option would result in an irrevocable loss of aura, and did he want to be the man who essentially destroyed Rodin’s final Thinker? The decision was made to accept the damage as constitutive to the sculpture’s contemporary reality, and concede that art cannot always exist protected from, or impervious to, the violence of the culture in which it is kept. David Franklin, a subsequent director of the museum, goes as far as to take conceptual ownership of the action, claiming it as “part of the piece, part of its history, part of the history of Cleveland.” And he’s right to do so. Unlike its brothers, the Cleveland Thinker bears the scares of its age, its dismembered form a troublesome image. The things that once made the body look strong – the powerful musculature of the torso and arms, the swelled veins and oversized hands – now make the figure look fleshy, grotesque, helpless. There is an additional darkness to the figure’s contemplations, a newer, more modern sense of dread. Built in 1902 and bombed in 1970, it has become a powerful representation of those turbulent years in-between. It’s hard to think what the bombing meant, what the perpetrators had hoped to achieve, and why the Thinker was targeted. It was high profile, sure, but hardly a symbol of autocratic or imperialist repression, and, unlike Guernica, a seemingly apolitical piece of art. Maybe that was the reason: its apparent apathy, its lack of commitment, its quiet contemplation in the face of rampant social injustice; was this the motivating factor or was it more mindless or impulsive or simply a good-idea-at-the-time? We don’t and won’t know. Whether intentional or not, the Cleveland bomb has written a new narrative into the history of the Thinker, adding further complexity to the original proposition. This can be appreciated guilt-free, because there are still Thinkers that remain intact.

THESE various participatory actions can be labelled as what Michel de Certeau calls tactics – small, individual actions, which occur in opposition to large-scale, bureaucratic and corporate strategies. As de Certeau sees it, strategies create institutional space – which are ideological and social, as well as physical – while tactics respond to such space: “Strategies are able to produce, tabulate, and impose these spaces . . . whereas tactics can only use, manipulate, and divert these spaces.” The individual, incapable of constructing his or her own space, must improvise, developing and employing short-term alternatives and counter-measures. The small, unaffiliated group of perpetrators in this essay are not the wild human herds Canetti writes of in ‘Crowds and Power’, maddened by a group lust for destruction, intoxicated by a moment where “the individual feels that he is transcending the limits of his own person.” No-one I’ve written about here is transcending or trying to, and if there is madness, then it only appears as madness because it is driven by a strong, deeply personal logic, not a sense of agentic solidarity. This is the opposite motion to the one Canetti outlines: these actions isolate and marginalize the perpetrator, furthering the distance between him- or herself and society at large. There will always be those who do not consent with common norms and social conventions. And there will always be rogue constituencies that despise parts of society with an intense, sometimes pathological, hatred. If art is worth anything, then in art they’ll find what they despise.